Overview

Evolution is the ongoing story of how life changes over time. Populations slowly shift in their traits as a result of three key ingredients: variation among individuals, the inheritance of traits, and differences in survival and reproduction. You can imagine a population as a deck of cards (the gene pool) where shuffling, drawing, and swapping cards over generations produces new combinations of traits. The processes that shuffle and sort these cards include:

- Mutation: The source of new cards, creating novel traits that may appear in a population for the first time.

- Natural selection: The rules of the game, determining which cards give an advantage in a given environment and are more likely to be passed on.

- Genetic drift: Random changes in which cards get passed on, especially important in small populations where chance can outweigh selection.

- Migration/gene flow: Cards moving between decks, mixing genetic material from different populations and introducing new variation.

- Recombination: The mixing of cards during reproduction, creating novel combinations of traits in offspring.

Big idea: Evolution has no ultimate direction or final goal. It is a continuous process driven by the environment, biological constraints, and chance events. The modern synthesis combines Darwin’s ideas about natural selection with Mendel’s principles of heredity, giving us a framework to understand and predict how allele frequencies in populations change over time.

Mendelian Genetics

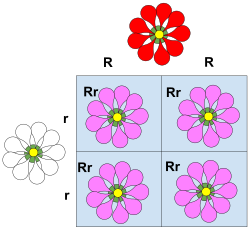

Gregor Mendel showed that traits are passed as discrete units called genes, and that each individual carries two versions of a gene, known as alleles. These alleles can interact in predictable ways, which allows simple Mendelian inheritance to make clear predictions about offspring. In most cases, a dominant allele will mask the effect of a recessive allele in a heterozygous individual. There are also variations such as codominance, where both alleles contribute to the phenotype equally, and incomplete dominance, where the heterozygote shows an intermediate trait.

- Law of Segregation: During gamete formation, the two alleles for a gene separate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene.

- Law of Independent Assortment: Genes for different traits can segregate independently during the formation of gametes.

- Alleles and genotype: Each individual carries two alleles for every gene, one inherited from each parent. The combination of these alleles is called the genotype.

- Dominance patterns: Complete dominance, incomplete dominance, and codominance produce different phenotypic outcomes based on how alleles interact.

Punnett squares provide a simple visual way to predict how parental alleles combine in offspring. For instance, a cross between two heterozygotes (Aa × Aa) will produce the genotypes AA, Aa, Aa, and aa in a 1:2:1 ratio. The resulting phenotypes depend on the dominance relationships of the alleles, allowing us to anticipate which traits are likely to appear in the next generation.

.png)

Extensions

When multiple genes influence traits (polygenic inheritance) or genes are linked on the same chromosome, inheritance patterns become richer. Linkage reduces independent assortment and generates non-Mendelian ratios unless crossing-over recombines alleles.

Checkpoint

- For a monohybrid cross Aa x Aa, what is the expected genotypic ratio?

- Which example best illustrates codominance?

- If two genes are genetically linked (close on same chromosome), what change would you expect in a dihybrid cross?

- Which set lists the four genotypes you would place inside a 2x2 Punnett square for Aa x Aa?

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium & Allele Frequencies

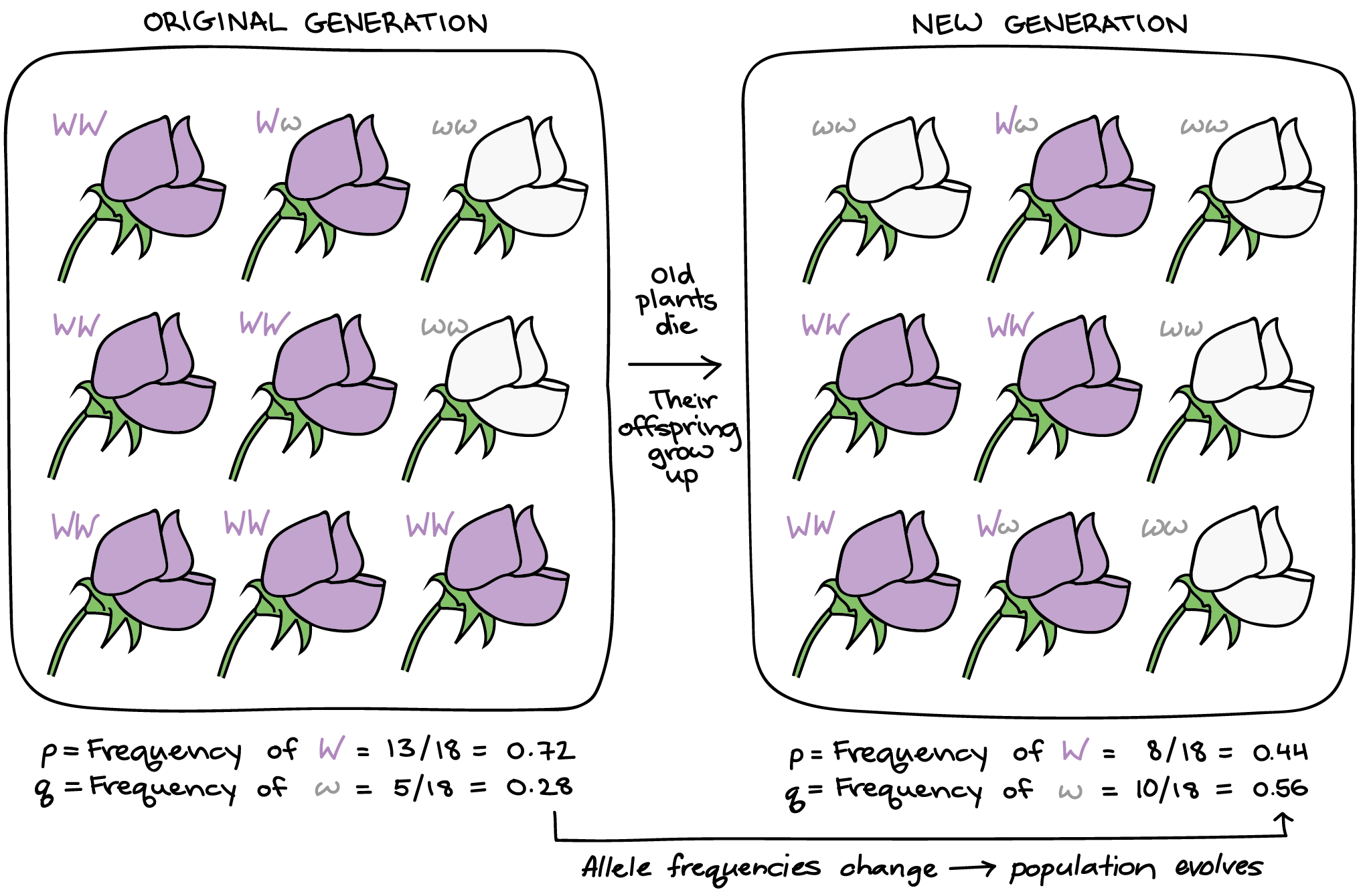

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium provides a simple null model for understanding populations. It shows what happens to allele and genotype frequencies when nothing unusual is occurring. Specifically, if there is no natural selection, mutation, migration, or genetic drift, and if mating is random, the frequencies of alleles and genotypes remain constant from one generation to the next. This makes it a useful baseline for detecting evolution.

In a system with two alleles, the frequencies of each allele are represented by p and q. The expected genotype frequencies can then be predicted using the formulas p² for the homozygous dominant, 2pq for the heterozygote, and q² for the homozygous recessive. If the observed genotype frequencies deviate from these predictions, it is a signal that one or more evolutionary forces are acting on the population.

Why it matters: Hardy–Weinberg is commonly used to estimate the frequency of carriers for a recessive trait when the prevalence of the trait is known. It also serves as a statistical baseline: if observed frequencies differ significantly from expected values, it suggests that evolution is occurring at that gene. Keep in mind that the model relies on assumptions that are rarely met completely in real populations, which is why it is most useful as a conceptual and analytical tool rather than a literal description of natural populations.

Worked example

If 9% of a population shows the recessive phenotype (aa), q² = 0.09 so q = 0.3 and p = 0.7. Expected heterozygotes = 2pq = 0.42 (42%).

Checkpoint

- If q² = 0.04, what are q and p?

- Which list correctly contains the five conditions required for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium?

- Which biological scenario would most likely cause departure from Hardy–Weinberg proportions?

Natural Selection & Adaptation

Natural selection is the process by which traits that improve survival or reproduction become more common in a population over time. Evolution acts on populations, not individuals, because heritable differences among individuals determine which traits are passed to the next generation. Traits that increase fitness are more likely to be transmitted, while less advantageous traits may decline. Fitness, represented as w, measures an individual's reproductive success. The selection coefficient, s, quantifies how much less fit a genotype is compared to a reference genotype, using the formula w = 1 − s.

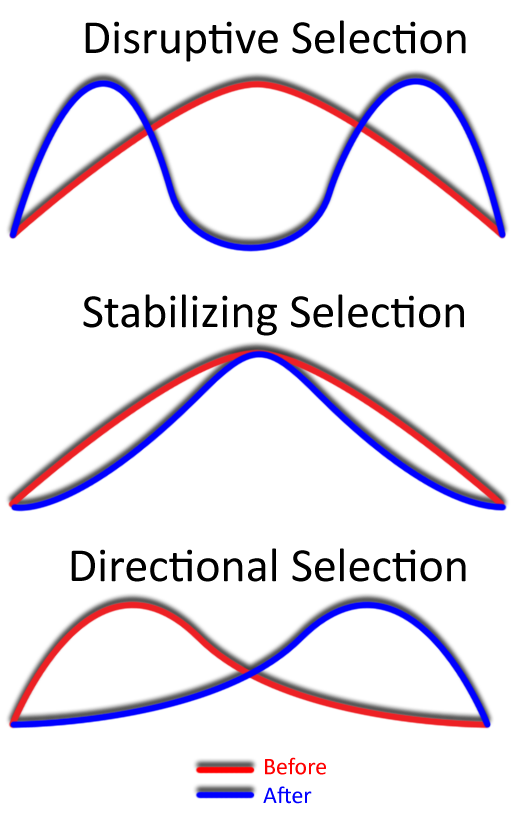

Natural selection can act in several distinct ways. Directional selection favors one extreme of a trait, causing the population average to shift. Stabilizing selection favors intermediate traits, reducing variation and maintaining the status quo. Disruptive selection favors individuals at both extremes, which can increase variation and sometimes lead to the formation of distinct subpopulations.

Adaptation in real populations reflects a dynamic balance between natural selection and other evolutionary forces. Mutation provides new genetic variants, gene flow introduces variation from other populations, and genetic drift produces random changes, especially in small populations. Together, these processes shape how populations evolve and adapt to changing environments over time.

Checkpoint

- What does a selection coefficient s = 0.1 mean for a genotype's fitness?

- Which is a classic real-world example of directional selection?

- Why are small populations more affected by genetic drift than large populations?

Phylogenetics & Tree Building

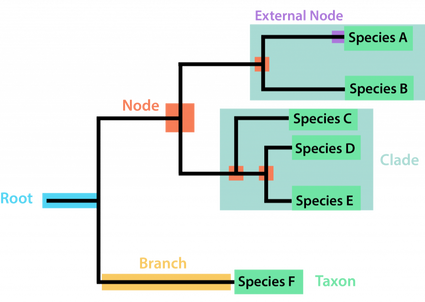

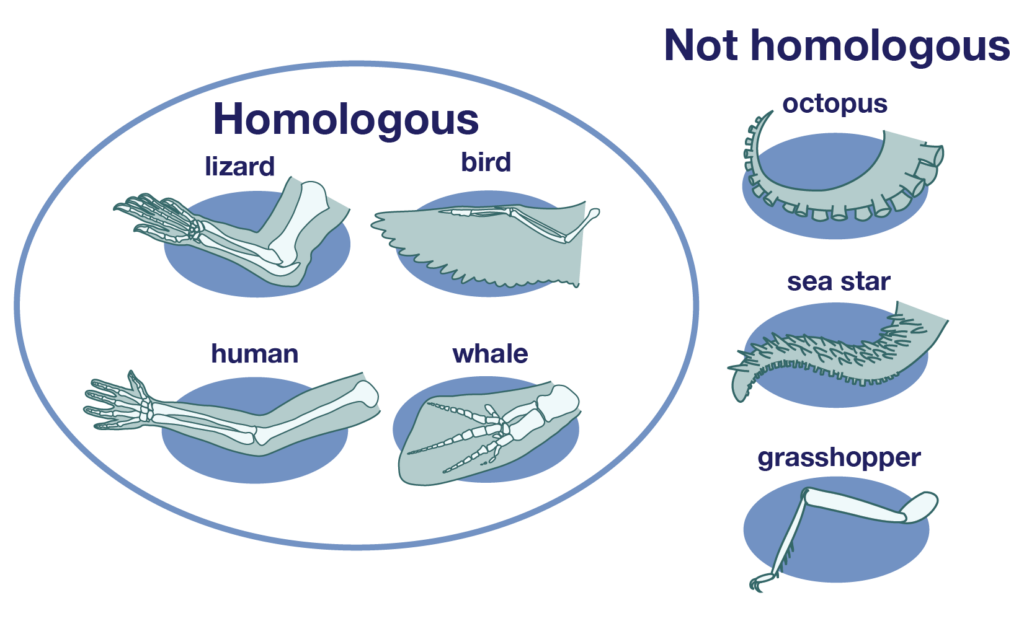

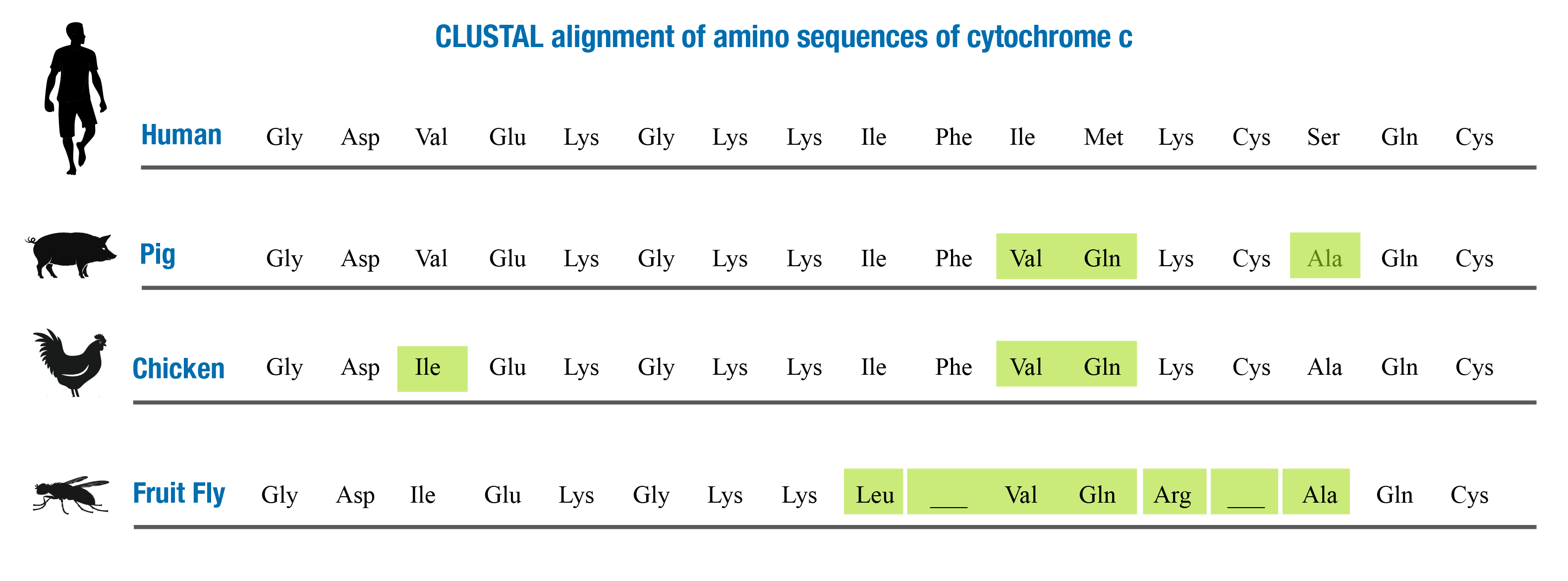

Phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relationships, helping us understand which species or populations are more closely related. Researchers use shared traits, which can be morphological (physical features) or molecular (DNA, RNA, or protein sequences), to reconstruct these relationships. A phylogenetic tree is a diagram that represents a hypothesis about ancestry and the order in which lineages diverged. Traits that are homologous reflect shared ancestry, while analogous traits, which arise independently through convergent evolution, can sometimes mislead analyses if not recognized.

There are several methods for building phylogenetic trees. Quick, distance-based approaches estimate relationships based on overall similarity, while more rigorous model-based methods, such as maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference, explicitly model how sequences evolve over time. Parsimony seeks the tree that requires the fewest evolutionary changes, assuming simplicity. Model-based methods, by weighing different evolutionary scenarios and accounting for rates of change, often produce more accurate trees when working with molecular data.

Understanding phylogenetics allows scientists to trace the evolutionary history of life, identify patterns of diversification, and make predictions about traits in species that have not been directly studied. By carefully choosing traits and methods, researchers can minimize errors caused by convergence and other confounding factors.

Important: topology (branching order) is the main message of a tree; branch lengths may encode genetic change or time depending on the analysis.

Checkpoint

- Which pair correctly matches homologous and analogous traits?

- In parsimony-based tree building, what is being minimized?

- What is one advantage of model-based (likelihood/Bayesian) methods over parsimony?

Speciation & Macroevolution

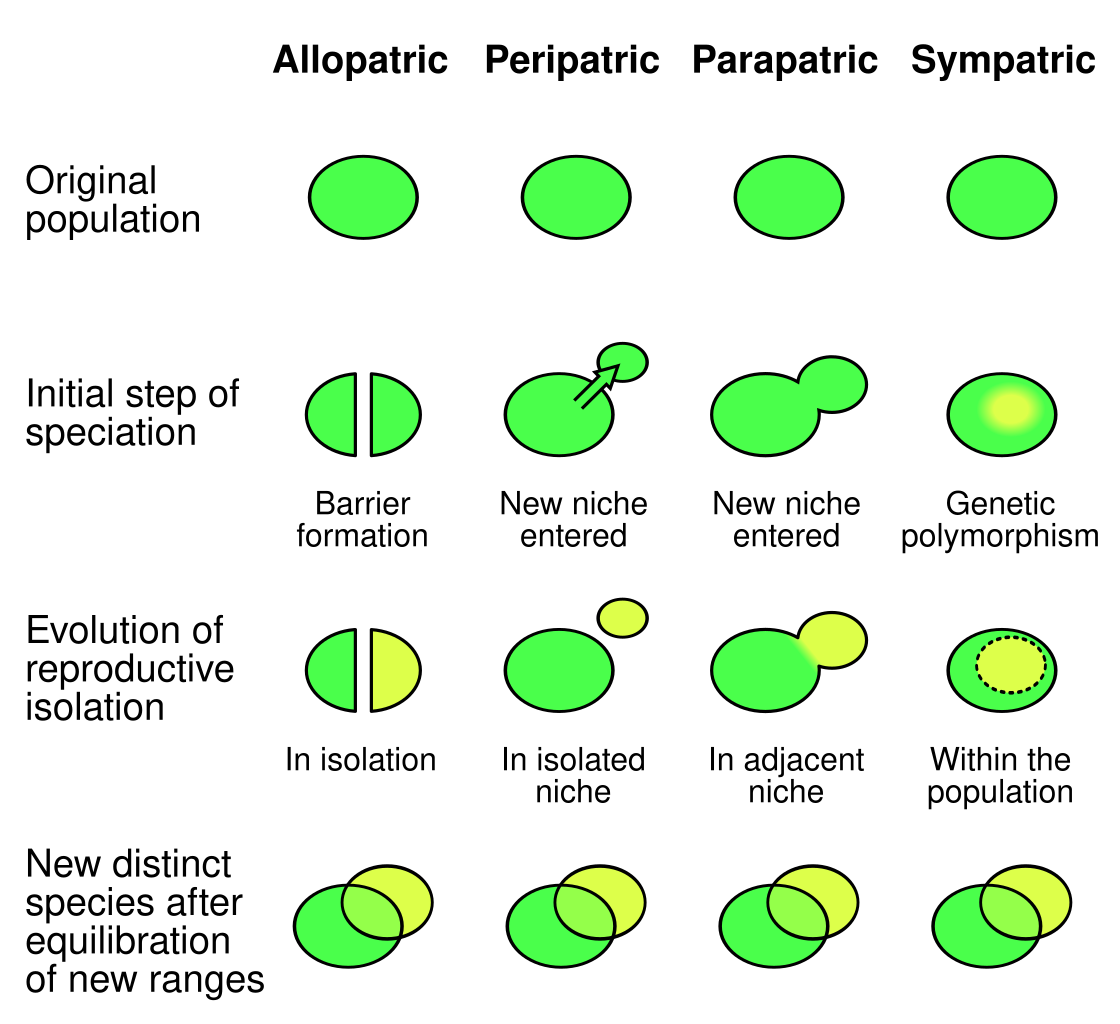

Speciation is the process by which one lineage splits into two or more reproductively isolated lineages. Geographic separation often drives this process, called allopatric speciation, where physical barriers like mountains or rivers prevent gene flow. Speciation can also occur without physical separation. In sympatric speciation, new species arise within the same area, such as through polyploidy in plants. Parapatric speciation occurs along environmental gradients. Over long timescales, repeated speciation events generate the macroevolutionary patterns we see in the fossil record and the tree of life.

Reproductive isolation is maintained by mechanisms that prevent gene flow. Prezygotic barriers act before fertilization (behavioral, temporal, mechanical, or gametic), while postzygotic barriers act after fertilization, reducing hybrid viability or fertility. New species often arise through a mix of selection, drift, and changes in mating systems or chromosome number.

Studying speciation and macroevolution helps explain the diversity of life and how species originate and diverge over time.

Checkpoint

- Which example best illustrates allopatric speciation?

- What is polyploidy and how can it cause instant speciation in plants?

- Which two are examples of prezygotic isolating mechanisms?

Evidence for Evolution

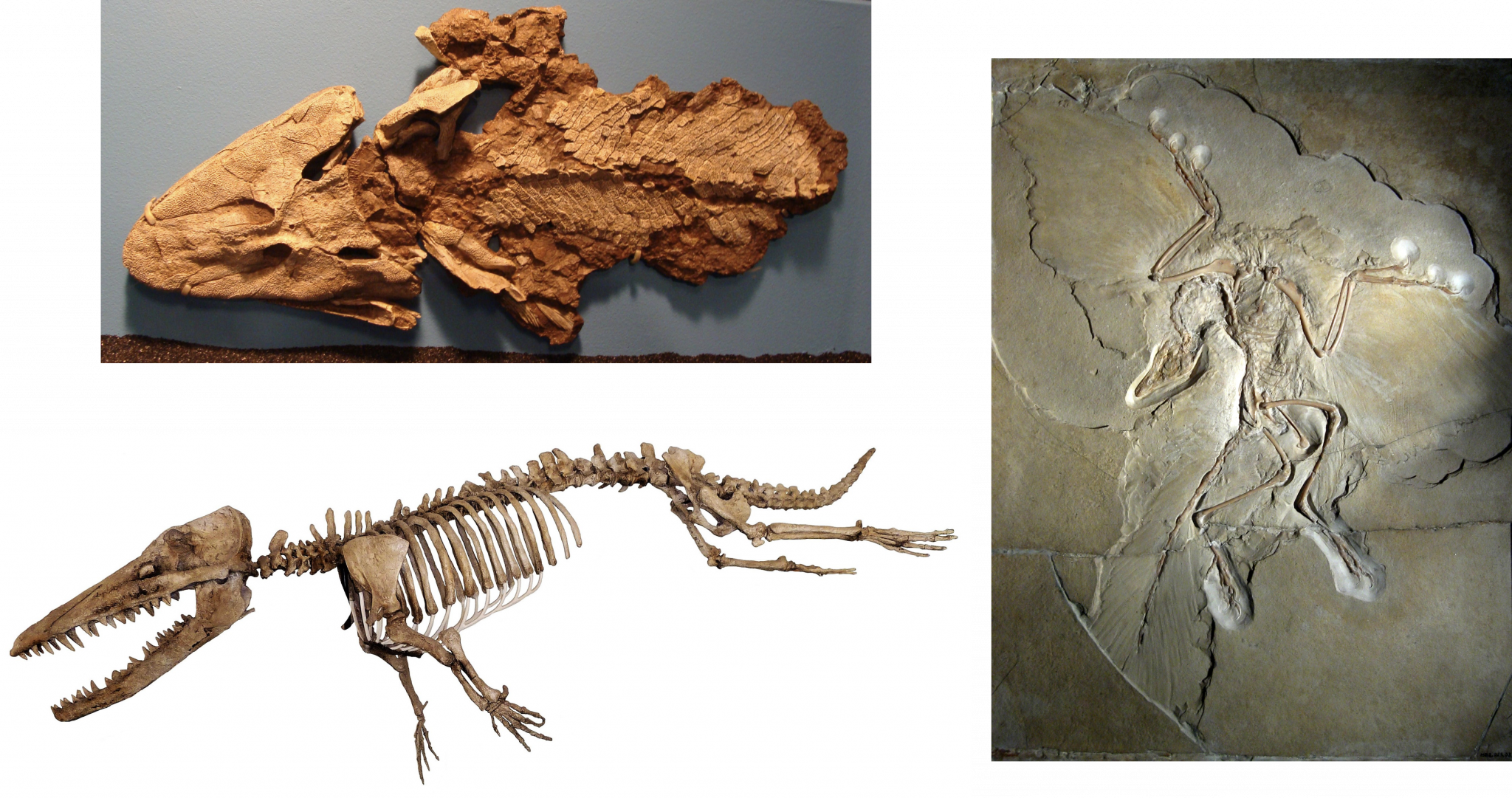

Multiple independent lines of evidence converge on the same conclusion: life has evolved. The fossil record shows transitional forms and changing assemblages through time. Comparative anatomy reveals homologous structures and vestigial traits. Biogeography explains distributions through history and plate tectonics. Molecular biology provides direct measures of relatedness via DNA and protein similarities. Finally, contemporary examples — such as antibiotic resistance, pesticide resistance, and lab evolution experiments — show evolution happening today.

- Fossils: snapshots of past forms, including transitional morphologies.

- Comparative anatomy: homologous structures and vestiges tell a story of descent.

- Molecular data: sequences let us quantify relatedness and timing.

- Direct observation: rapid evolution in response to strong selective pressures.

Checkpoint

- How do vestigial structures provide evidence for evolution?

- How does molecular sequence data support phylogenetic relationships?

- Which is a recent real-world example of observed evolution?

Further Reading & Resources

If you want to explore evolution more deeply, there are excellent textbooks and online resources available. Classic textbooks like Evolution by Futuyma and Principles of Population Genetics by Hartl & Clark provide detailed explanations of core concepts. Online resources such as NCBI for molecular biology data and Tree of Life for phylogenetics give interactive ways to explore evolutionary relationships. Primary literature is also valuable for seeing how these ideas are applied in research today.

Practice is essential for understanding evolutionary concepts. Work through Punnett squares, solve Hardy–Weinberg problems, and try building small phylogenetic trees from mock sequence data or freely available online datasets to see the processes in action.

- Textbooks:Evolution by Futuyma; Principles of Population Genetics by Hartl & Clark.

- Web Resources: NCBI; Tree of Life; tutorials on Khan Academy Genetics and Nature Evolution Articles.

- Activities: hands-on Punnett squares, Hardy–Weinberg calculations, and simple phylogenetic reconstructions.

Final Checkpoint

- Which statement best summarizes how mutation, selection, drift and migration interact to shape evolution?

- Which is a practical, small research question you could test in a lab or field project related to evolution?